The U.S. 9th Armored Division in the Liberation of Western Czechoslovakia 1945

By Bryan J. Dickerson*

Introduction

On the morning of 7 May 1945 and as the Third Reich collapsed, soldiers of Combat Command A (CCA), U.S. 9th Armored Division mounted up their vehicles and resumed their advance eastward further into north-western Czechoslovakia. Temporarily attached to the 1st Infantry Division, CCA’s mission was to liberate the Czech city of Karlovy Vary. CCA’s task forces rolled forward against negligible German resistance. Nevertheless, after only a couple hours, higher headquarters radioed orders for CCA to halt its forces in place. The German High Command had surrendered. The Second World War in Europe was over. During its final attack of World War Two, the 9th Armored Division was brought to a stop just a few miles short of its last objective.

Activation of the 9th Armored Division

During World War Two, the United States Army organized and equipped sixteen armored divisions, all of which deployed to the North African – European Theater of Operations. These armored divisions participated in the North African campaigns, the invasion of Sicily, the Italian campaign, the liberation of western Europe and the conquest of Germany. The armored divisions brought tremendous mobility, firepower and organizational flexibility onto the battlefields, and helped greatly in assisting in the destruction of the Third Reich.

In forming its armored divisions, the U.S. Army employed two methods for organization. Initially, all U.S. armored divisions were organized as “Heavy” divisions with twice as many tank units as infantry units. Only the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions used the “Heavy” organizational scheme in combat. Battlefield experience showed the Army that a greater balance of combat forces was needed. In September 1943, the Army adopted the “Light” Armored Division organization and re-organized nearly all of its armored divisions using this method. Only the 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions retained the “Heavy” Armored Division organization.[1]

The “Light” Armored Division organization was designed to address the shortages of infantry in the “Heavy” Armored Division organization. The “Light” Armored Division utilized a Division Headquarters, three Combat Command (A, B and Reserve) Headquarters and thirteen organic battalions. Each armored division contained three battalions each of tanks, armored infantry and armored field artillery as well as a mechanized cavalry squadron for reconnaissance, and armored engineer, armored medical and armored ordnance battalions. “Light” Armored Divisions were further bolstered by permanently assigned tank destroyer and self-propelled anti-aircraft artillery battalions and other support units as needed.[2]

The “Light” Armored Divisions had an authorized strength of 10,670 personnel. The division’s primary offensive combat power was provided by its tanks and armored vehicles. The armored division was authorized 195 M-4 medium tanks mounting either 75mm or 76mm guns, 77 light tanks, fifty-four self-propelled artillery pieces and 466 half-tracks. The light tanks were either M-5s which mounted a 37mm main gun or the much improved M-24 Chaffee which had a 75mm main gun. Artillery fire support was provided primarily by M-7 self-propelled guns with 105mm howitzers. Each tank battalion also had a number of M-4 tanks containing short-barreled 105mm howitzers instead of 75mm or 76mm guns in their turrets. Half-tracks transported the infantry and performed a variety of support roles. The cavalry squadron contained light tanks and armored cars. Attached tank destroyer battalions were equipped with either the M-10, M-18 or M-36 tank destroyers, mounting 75mm, 76mm or 90mm anti-tank guns respectively in open-topped turrets.[3]

The 9th Armored Division traced its origins back to the 2nd Cavalry Division stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas. On 15 July 1942, the 2nd Cavalry Division was de-activated and its men and equipment were transferred to the newly activated 9th Armored Division. Thus the 9th Armored Division had a high percentage of Regular Army officers and soldiers who had served in the horse cavalry. The new armored division was organized according to the Table of Organization for the “Heavy” Armored Division. In October of 1943, the 9th Armored Division was re-organized according to the new “Light” Armored Division Table of Organization.[4]

The 9th Armored Division’s first commanding general was Major General Geoffrey Keyes, assisted by Brigadier Generals Ernest Harmon and John W. Leonard. In the fall of 1942, Keyes was transferred to serve as Deputy Commander of the II Armored Corps and Harmon became commanding general of the 2nd Armored Division for the North Africa invasion. Brigadier General Leonard was promoted to Major General and became the new commanding general of the 9th Armored Division. Leonard was a 1915 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy and a classmate of Omar Bradley and Dwight Eisenhower. He had served in General John Pershing’s expedition into Mexico in 1916 and been a combat-decorated battalion commander in France during World War One. Prior to joining the 9th Armored Division in the summer of 1942, Leonard was a regimental commander with the 1st Armored Division.[5]

Lieutenant Colonel Leonard Engeman from Minnesota was an Army Reservist activated for World War Two in 1941. He was assigned to the 2nd Horse Cavalry at Fort Riley. When the 9th Armored Division was activated, Lt Col Engeman became part of the new division and was placed in command of its 14th Tank Battalion in the summer of 1944.[6]

Also in the 14th Tank Battalion were 1st Lieutenant Demetri “Dee” Paris and Captain Cecil Roberts. Dee Paris enlisted in the Army in September 1942 and earned a commission through Officer Candidate School. He joined the 9th Armored Division in March 1943 and was a Platoon Leader with D Company. D Company contained the battalion’s light tanks. Cecil Roberts received his commission through the Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) in early 1941 and soon after went on active duty. He eventually became the S-3 (Operations) Officer for the 14th Tank Battalion.[7]

Lt Col George Ruhlen from San Diego, California, was the commander of the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. He earned his officer commission from the U.S. Military Academy. He served in several horse artillery units before being assigned to the 9th Armored Division.[8]

After the U.S. Army adopted the “Light” Armored Division Table of Organization in September 1943, the 9th Armored Division was re-organized accordingly. Thus, the 9th Armored Division now consisted of:

Division Headquarters and Headquarters Company

Headquarters and Headquarters Company / Combat Command A

Headquarters and Headquarters Company / Combat Command B

Headquarters and Headquarters Company / Combat Command R

Headquarters and Headquarters Battery / 9th Armored Division Artillery

Headquarters and Headquarters Company / 9th Armored Division Trains

2nd Tank Battalion

14th Tank Battalion

19th Tank Battalion

27th Armored Infantry Battalion

52nd Armored Infantry Battalion

60th Armored Infantry Battalion

3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion

16th Armored Field Artillery Battalion

73rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion

89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron [Mechanized]

2nd Armored Medical Battalion

131st Armored Ordnance Maintenance Battalion

Military Police Platoon

Division Band

9th Armored Engineer Battalion

149th Armored Signal Company

Between June 1943 and August 1944, the 9th Armored Division participated in several major training exercises, including one in the deserts of California. After its desert exercises, the division was transferred to Camp Polk, Louisiana. In August 1944, the division travelled east from its base in Louisiana to New York. It's men boarded the cruise ship Queen Mary and set sail for Britain.[9]

On 27 August 1944, the 9th Armored Division landed in Britain and prepared for operations on the European Continent. The division was able to secure the new M4A3 Sherman tank with its improved engine and 76mm main gun. Though still inferior to the main guns of the German medium and heavy tanks, the 76mm represented an improvement over the short-barreled 75mm gun then standard on Sherman tanks. One month later on 25 September 1944, the division arrived in France.[10]

The arrival of the 9th Armored Division, nicknamed “Phantom”, in France came 111 days after D-Day. In those preceding days, the U.S. Army and the Allied Expeditionary Force had landed in Normandy, fought a brutal campaign in the hedgerows, broken through the German lines and pursued the disintegrating German Army across France and into Belgium, Luxembourg and Holland. In making their rapid advance across France, however, the Allied leadership made what must be regarded today as some questionable command decisions even as their armies far outstretched their supply lines. This enabled the Wehrmacht to re-organize and re-form an effective defense along the western German borders. Combat during the fall of 1944 thus developed into a grinding battle of attrition amidst worsening weather conditions on Germany's western front.[11]

For its part the U.S. 9th Armored Division became part of the VIII Corps of the First U.S. Army located in the Ardennes Region of Belgium and Luxembourg. This heavily forested and mountainous region was being used by the Twelfth U.S. Army Group to refit and rest divisions that had experienced heavy combat; and to give new inexperienced divisions some light combat experience in a relatively “quiet” sector of the front lines. In November, the 482nd Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion (Self-Propelled) and 811th Tank Destroyer Battalion were attached. Here in the Ardennes, the 9th Armored Division’s three combat commands were split up and used to augment other divisions in the area.[12]

The 9th Armored Division was still operating as three separate units when the last great German counter-offensive of the war, a struggle that wold become known in the U.S. Army as the Battle of the Bulge, struck U.S. positions in the Ardennes during December. Combat Command B helped delay the Germans at St. Vith. Reserve Command delayed the German drive on Bastogne and then fought with the 101st Airborne Division in defending the vital crossroads town. Combat Command A fought on the southern shoulder of the Bulge. While fighting to enlarge and defend the Bastogne Corridor, Combat Command A was temporarily attached to the 4th Armored Division as Combat Command X.[13]

After the Battle of the Bulge, the 9th Armored Division re-organized and then returned to active operations in February 1945. The division also received the 656th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Then on 7 March 1945, a task force of the 9th Armored Division captured the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen on the Rhine River – the last great geographical barrier blocking the Allies from pouring across Germany. The capture of the intact Ludendorff Bridge enabled U.S. forces to quickly cross the Rhine River and establish a firm bridgehead for follow-on operations. The division’s capture of the only intact bridge across the Rhine forced a change in Eisenhower’s plans. Other U.S. divisions were rushed across the bridge and subsequent bridges erected in the vicinity to exploit this fortunate opportunity. By the end of March, all Allied armies had crossed the Rhine.[14]

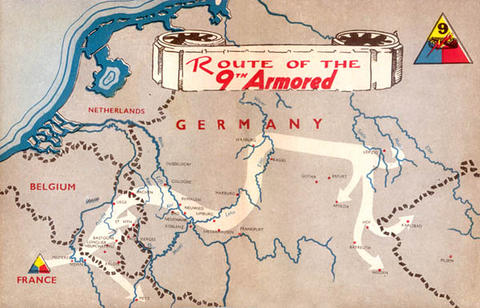

Breaking out from the Remagen bridgehead, the 9th Armored Division struck out across central Germany. Over the next twenty-seven days, the division advanced over 200 miles through central Germany, and captured Neiderhausen, Idstein, Warburg, and Colditz on its way to the Mulde River. In doing so, the division set the stage for the 2nd and 69th Infantry Divisions to capture the city of Leipzig.[15]

The month of April witnessed the near collapse of the German Army in the west. Allied armored and mechanized forces rushed across central Germany. The Allies also discovered the atrocities of the Nazi concentration camps at such infamous places as Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen and Dachau. By mid-April, the capture of Berlin seemed within reach of British and American led armies. Eisenhower, however, recognized that the Soviets were in a far better position to capture the city so he directed his massive army to halt well short of the city. Meanwhile, American and French forces overran southern Germany and pushed into Austria.[16]

On 18 April, elements of the 90th Infantry Division of General George S. Patton’s Third U.S. Army reached the 1937 Czechoslovak - German border and crossed into the Nazi-occupied Allied nation. Eisenhower’s primary focus was to prevent the formation of the “National Redoubt” (Alpine Festung) area of last ditch fanatical Nazi resistance rumoured to be occurring in southern Germany and western Austria. So after reaching the Czechoslovak border, Eisenhower turned Third U.S. Army to the south-east and pointed it towards Austria.[17]

For the rest of the month, XII Corps of Third U.S. Army advanced parallel to the border as it protected the army’s left flank during the drive to Austria and conducted several cross-border operations. The 2nd Cavalry Group liberated the border town of Asch and the 97th Infantry Division liberated the city of Cheb. 2nd Cavalry Group also undertook two daring raids to rescue Allied prisoners of war and to rescue the famed Lippizzaner performing horses of the Spanish Riding School from behind enemy lines. The 90th Infantry Division liberated the Floessenbuerg Concentration Camp. By month’s end, Third U.S. Army held positions along and over the Czechoslovak border and were driving into Austria.[18]

With every mile that Third U.S. Army advanced south its left / western flank along the Czechoslovak - German border grew longer. This placed greater and greater strains on the 90th and 97th Infantry Divisions and 2nd Cavalry Group to cover this ever-lengthening flank. At the end of April, Twelfth U.S. Army Group decided to have First U.S. Army accept some responsibility for the Czechoslovak border in order for Third Army to continue its drive into Austria.[19]

First U.S. Army’s V Corps was tasked to assist Third Army along the Czechoslovak border. But at this time, V Corps were occupying a static front along the Elbe River. Transferring V Corps down to the Czechoslovak border required a shuffling of units. The 9th Armored Division was gained from VIII Corps. After this was accomplished, V Corps consisted of Major General Clarence Huebner’s corps headquarters, nine battalions of field artillery, seven battalions of anti-aircraft artillery, four independent tank battalions, five independent tank destroyer battalions, two engineer combat groups, numerous support units, the 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, the 2nd Ranger Battalion, the 17th Belgian Fusilier Battalion, the 102nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Group [Mechanized], and the 1st, and 2nd Infantry, and the 9th Armored Divisions. As May began, each of these divisions was in motion for its new positions. In addition, the 97th Infantry Division was gained from XII Corps.[20]

Major General John W. Leonard was still in command of Phantom Nine. Brig. Gen. Thomas L. Harrold’s Combat Command A consisted of Lt. Col. Kenneth Collins’s 60th Armored Infantry Battalion, Lt. Col. Leonard Engeman’s 14th Tank Battalion, and Lt. Col. George Ruhlen’s 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. The 52nd Armored Infantry Battalion, the 19th Tank Battalion, and 16th Armored Field Artillery Battalion comprised Col. Harry W. Johnson’s Combat Command B. Johnson had assumed command after Major General William Hoge had left the division to assume command of the 4th Armored Division in late March. Reserve Command, under command of Lt. Col. Farris N. Latimer, was made up of the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, the 2nd Tank Battalion and the 73rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. Latimer was new to the job, having only been placed in command on 28 April. Detachments from other units such as the 2nd Armored Medical Battalion, the 656th Tank Destroyer Battalion, the 482nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion, the 131st Armored Ordnance Maintenance Battalion, the 9th Armored Engineer Battalion, and the 89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron [Mechanized] rounded out the combat commands. Other 9th Armored Division units were the 149th Armored Signal Company, the 509th Counter-Intelligence Corps Detachment and the Military Police Platoon.[21]

Lt. Col. Engeman’s 14th Tank Battalion had three companies of M4A3 Sherman medium tanks and a company of M24 light tanks. The battalion had had five of the new M26 Pershing tanks, equipped with the 90mm cannon, but traded them in early April 1945 to the 19th Tank Battalion for five M4A3 Shermans. “This was done because the M26 tracks were so wide they could not cross obstacles on the U.S. Army treadway bridging,” recalled the battalion operations officer Capt. Cecil Roberts. According to him, the speed of advance was more important than the German tank threat at this time.[22]

On 1 May, the three battalions of Combat Command A were in reserve in and around Jena, Germany. There they conducted training and performed maintenance on their vehicles. C Company of the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion captured a few German soldiers in its area. “The rest of the battalion was in a sort of victory mood,” wrote Paul M. Crucq in his history of the battalion. “For the first time since the battalion entered combat on March 1 at Wollersheim the men’s morale was excellent.” Like the rest of the 9th Armored Division, the soldiers of Combat Command A believed that their war was over and that they soon would be assigned to occupation duties in Germany.[23]

The reserve status of Combat Command A, however, was soon to end. Its parent division was being ordered to an assembly area near Weiden, Germany. Apparently, for parts of the 9th Armored Division, the war was not yet over.

The Situation in Early May 1945

The 1937 Czechoslovak – German border region was mountainous and heavily wooded; which channelized vehicular movement through defensible mountain passes and gaps. Once through these mountains, the terrain leveled out into rolling farmland and the road network improved significantly. The region’s most important cities were Plzen and Cheb. Plzen boasted the massive Skoda Works industrial complex. Both Cheb and Plzen had airports that were being utilized by the remnants of the German Luftwaffe.

The German forces operating in Czechoslovakia belonged to three major commands: General Hans von Obstfelder’s 7th Army, General Rudolf Toussaint’s Wehrkreis (Military Area) Prague, and Field Marshall Ferdinand Schoerner’s Army Group Center. The 7th Army was responsible for defending the German – Czechoslovak Border. To do so, General von Obstfelder had the severely depleted 2nd Panzer Division, Wehrkreis XIII (training and replacement command absorbed into the 7th Army), an engineer brigade, an Officer Candidate School, the 12th Corps, and the 11th Panzer Division. Both panzer divisions were short on tanks, fuel and other supplies. Only the 11th Panzer Division was near its authorized manpower strength. Wehrkreis Prague consisted of two divisions of regional defense troops guarding various locations of military importance in and around Prague. All other German forces in Czechoslovakia belonged to Army Group Center.[24]

The German commanders in Czechoslovakia suffered a tremendous blow on 4 May 1945. Earlier that week, Field Marshall Schoerner ordered the 11th Panzer Division east to fight the Soviets. The division’s commander, General Wend von Wietersheim, decided instead to spare his men years of brutal captivity in a Soviet prisoner of war camp and surrendered the bulk of his division to the American 90th Infantry Division. A few days later the rest of the division surrendered to the 26th Infantry Division further south.[25]

V Corps and the 9th Armored Division Head South

On 2 May, Brig. Gen. Harrold received orders from his Division Headquarters directing him to move south with the rest of the division. In the order of march, his command would follow the Reserve Command in one column; the rest of the division would march in another column. Once Combat Command A reached its designated assembly area, it would be temporarily attached to the 1st Infantry Division in north-western Czechoslovakia.[26]

With a return to offensive operations imminent, Brig. Gen. Harrold formed his command’s usual task force arrangements. This entailed swapping units between the tank and armored infantry battalions. Thus formed, Task Force Collins consisted of a platoon of A Company, 9th Armored Engineers Battalion and the bulk of Collins’s own 60th Armored Infantry minus A Company which had been traded to the 14th Tank Battalion for its C Company. Task Force Engeman consisted of his 14th Tank Battalion minus C Company, A Company of the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion, a section of quad fifty-caliber machine gun half-tracks from the 482nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery [Automatic Weapons] Battalion and a platoon from the 9th Armored Engineers Battalion’s A Company. Lt Col George Ruhlen’s 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion would support both task forces with their 105mm self-propelled guns. These formations were completed that afternoon; from this, the men knew that they were headed back into combat.[27]

Late that night, Harrold issued orders to his command for the movement south. He specified the intervals between units and vehicles, the route and times. Company C of the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron would led the command’s column followed by Task Force Collins, the Command Headquarters, armored engineers, tank destroyers, anti-aircraft artillery, the 3rd Armored Field Artillery, Task Force Engeman, the medical company and the command’s supply and maintenance units.[28]

Early on the morning of Thursday, 3 May, Lt. Colonels Collins and Engeman assembled their respective officers and issued orders for the march south. Then they waited for Reserve Command. At around 1045, Combat Command A began its march and headed south along the Autobahn from Jena to Hirschberg with Company C of the 89th Reconnaissance Squadron in the vanguard. At Hirschberg, the command turned on to secondary roads. Soldiers from the reconnaissance unit were used to mark the route to the assembly area located near Arzberg. As 3 May ended and 4 May began, Combat Command A’s units were just pulling into their new positions.[29]

As the 4th of May dawned, V Corps was still in the process of assembling its divisions for the expected push into Czechoslovakia. The 1st and 97th Infantry Divisions were already well-established on the border. On the Big Red One’s left was the 6th Cavalry Group of VIII Corps. The 102nd Cavalry Group was in reserve at Weiden. The 2nd Infantry Division was in the midst of relieving the 90th Infantry Division along the border. The 9th Armored Division was still moving south from Jena.[30]

Early on the morning of 4 May, the soldiers of the Combat Command A, 9th Armored Division arrived at their new assembly areas near the Czechoslovak border. The command dispersed with its Headquarters at Marktredwitz, Task Force Collins in and around Arzburg, and Task Force Engeman centered on Mitterteich. In getting here, they had traveled about 100 miles. They were now a part of the 1st Infantry Division. For the moment, they would constitute a reserve for the division and could only be committed on orders from the corps commander.[31]

While awaiting further orders, the men of Task Force Collins assumed tasks associated with occupation. They maintained law and order and conducted security patrols for their area. The men screened all German males of military age. They also arrested twenty-five suspected “Werewolves” in Arzburg. “Werewolves” were German soldiers who attempted to set up guerrilla operations behind the advancing Allied armies. To the south-east, the 14th Tank Battalion took up blocking positions to halt all movement from the east.[32]

Meanwhile, there was widespread belief amongst the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion that this was to be their assigned area of occupation. Radio reports indicated that the German Army was in shambles and only SS fanatics were continuing to resist in Czechoslovakia. The battalion began making the necessary arrangements for the creation of military government for their area.[33]

Combat Command A was now a part, albeit a temporary one, of the 1st Infantry Division. At 1000, the division issued a Letter of Instruction to the Command which detailed them to secure their areas of responsibility, construct roadblocks, patrol, and maintain law and order. C/89th Recon Squadron was to scout routes for the Command to the front lines held by the 18th Infantry Regiment. Particular emphasis was to be placed upon screening German males of military age for possible guerrillas or war criminals. Each unit was to search all buildings within its area of responsibility for weapons, demolitions, and radio communication equipment. Civilian movement was to be heavily restricted.[34]

Day of Decision – 5 May 1945

For the last several weeks, debate had been raging at the highest levels of the Allied High Command over whether or not to liberate western Czechoslovakia and more specifically, the capital city of Prague. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, senior British diplomats and military officers, the U.S. State Department and pro-democracy Czechs and Slovaks pressed for Third U.S. Army to liberate Prague and as much of western Czechoslovakia as possible as a possible counter-balance to Soviet machinations to install pro-Soviet Czech and Slovak Communists in power in the liberated country. General Eisenhower, however, did not want to hazard American lives for post-war political purposes and did not want to offend the Soviets. U.S. President Harry S. Truman and the U.S. Chiefs of Staff supported Eisenhower’s decision as the Theater Commander in Europe. Soviet Premier Josef Stalin, the Soviet High Command, and Czech and Slovak Communists all wanted a pro-Soviet Communist government installed in Czechoslovakia.[35]

By early May, the rapid and minimally opposed occupation of the National Redoubt area by Third and Seventh U.S. Armies had proven that the National Redoubt was nothing more than a figment of Nazi propaganda. Only in Czechoslovakia were the Germans still mounting serious resistance. So General Eisenhower decided to send Third U.S. Army to help the Soviets clear the remaining German forces out of Czechoslovakia. On 4 May, he sent a message to the Soviets informing them of his decision to send Third U.S. Army eastward to the line Karlovy Vary – Plzen – Ceske Budejovice with a possible further advancement to the west bank of the Vltava River. Since the Vltava River flowed through Prague, this implied a possible advance to liberate at least part of the Czechoslovak capital. Eisenhower also sent orders to Gen. Bradley for Third U.S. Army to conduct the operation.[36]

At 1930, Bradley telephoned Patton with Eisenhower’s orders to attack to the Karlovy Vary – Plzen – Ceske Budejovice line. In addition, Bradley transferred First U.S. Army’s V Corps to Third U.S. Army for Patton to use in his offensive. Patton immediately issued orders for V Corps and XII Corps to attack the following morning with their infantry divisions to open up routes for their armored divisions to pass through.[37]

V Corps’s commanding general Major General Clarence Huebner asked to use the more experienced 9th Armored Division for the Plzen attack instead of the 16th Armored Division. This was not a slight against the 16th Armored Division. The 9th Armored Division had fought in the Ardennes Counter-Offensive, seized the Remagen Bridge and driven across central Germany. With the war in Europe winding down, Patton, however, wanted to get the new 16th Armored Division into the final fight. So, 9th Armored Division would detach its Combat Command A to spearhead 1st Infantry Division’s drive on Karlovy Vary while the rest of the division was held in reserve.[38]

As planned, V Corps and XII Corps’s attacks into Czechoslovakia commenced early on the morning of 5 May 1945. In V Corps’s area, the 1st Infantry Division pushed east from the vicinity of Cheb, and the 2nd and 97th Infantry Divisions pushed east towards Plzen. In XII Corps’s area, the 359th Infantry Regiment of the 90th Infantry Division continued to process the surrendering 11th Panzer Division while the division’s other two regiments, and the 5th and 26th Infantry Divisions seized key terrain further south. By the end of the day, both corps were ready to unleash their armored divisions.[39]

Liberation Day – 6 May 1945

Early on the morning of Sunday 6 May 1945, V and XII Corps of Third U.S. Army renewed their drives into western Czechoslovakia with their armored divisions rushing through the forward positions of the infantry divisions. In V Corps’s area, the 16th Armored Division pushed through the forward lines of the 97th Infantry Division and liberated the city of Plzen. The 2nd and 97th Infantry Divisions followed behind, consolidating the 16th Armored Division’s gains and liberating numerous towns and villages. In XII Corps’s area, the 4th Armored Division pushed north-eastward through the mountain passes held by the 5th and 90th Infantry Divisions and headed for Prague. Further south, the 26th Infantry Division attacked to the north-east in the direction of Ceske Budejovice. Meanwhile the 11th Armored Division continued its drive in Austria. By the end of the day, numerous towns had been liberated, tens of thousands of German troops and civilians had surrendered and Eisenhower’s Karlovy Vary – Plzen – Ceske Budejovice restraining line had been reached in several places.[40]

In the north, the 1st Infantry Division and its attached armor from 9th Armored Division ran into the toughest German resistance experienced by Third U.S. Army in Czechoslovakia that day. The front lines of 1st Infantry Division were located about five kilometers east of Cheb. Task Force Engeman headed east from there with lightly armored reconnaissance vehicles in the lead while Task Force Collins awaited further orders.[41]

Task Force Engeman soon ran into German resistance from roadblocks, machine guns, anti-tank guns and infantry armed with Panzerfaust hand-held anti-tank rockets. The narrow road and rugged terrain greatly aided the German defenders. After the first resistance was overcome, the M24 light tanks of 1st Lt Demetri Paris’s platoon of D Company were placed in the lead. The reconnaissance vehicles were too lightly armored to withstand anti-tank guns and Panzerfausts.[42]

Near the town of Gelsdorf, the Task Force ran into more anti-tank guns, which knocked out the tank driven by Sgt. Arthur Critchlow. “The German Anti-Tank round struck the road pavement, ricocheted up through the bottom of the tank and killed driver Critchlow,” Lt Paris later recalled. “My tank was alongside. I fired and neutralized the AT gun, dismounted and went to Critchlow’s tank. I was devastated since he was one of my favorite soldiers.”[43]

C Battery of the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion immediately went into firing positions. Within minutes, the Battery hit the remaining German anti-tank guns with 105mm shells and knocked them out. The American column pressed on. Less than a thousand yards later, another M-24 light tank was struck by a German Panzerfaust anti-tank rocket and knocked out. Again, C Battery provided fire support as American infantrymen swept through the nearby woods and cleared out the few German defenders.[44]

Having overcome the German resistance, the Task Force resumed its advance and continued eastward. The task force halted for the night just a few miles east of Karlovy Vary outside the town of Sokolov. The advance had been costly. Two American light tanks had been knocked, one soldier had been killed and several more wounded.[45]

While Task Force Engeman was advancing on Karlovy Vary on 6 May, Task Force Collins remained in reserve at Cheb. Task Force Collins consisted of the bulk of the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion, a company of tanks from the 14th Tank Battalion and self-propelled guns from the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. Shortly before darkness, Task Force Collins received orders to move forward to the town of Steinhof. From here, Task Force Collins was to pass through Task Force Engeman’s positions the next morning and attack Karlovy Vary.[46]

The 7th of May 1945

While American forces pushed eastward throughout western Czechoslovakia, Czech partisans were waging their own battles in Prague. General Toussaint had decided to abandon the city and so had taken his forces west to surrender to the Americans. However, Field Marshall Schoerner had ordered SS troops into Prague to suppress the uprising. Unable to withstand the brutal SS attacks, the lightly armed Czechs cried out desperately by radio and messenger for American assistance. But despite the fact that the lead units of the 4th and 16th Armored Division were not meeting any German resistance on the roads leading to Prague, no assistance would be coming. At the request of the Soviet High Command, General Eisenhower agreed to halt Third U.S. Army at the Karlovy Vary – Plzen – Ceske Budejovice line and await the Soviet armies there. Those advanced U.S. units were recalled from their drive on Prague.[47]

There was another factor which would affect how far U.S. forces advanced on the day of 7 May 1945. In a school house in Reims, France, representatives of the Third Reich surrendered to the Allied Powers that morning. All hostilities were to cease at 0001 local time on 9 May 1945. General Eisenhower immediately ordered all of his forces to halt in place and not advance any further. As part of the surrender protocols worked out amongst the Allies, all German forces not within American lines prior to midnight 8 May 1945 belonged to the Soviets. Thus, hundreds of thousands of German soldiers and civilians became engaged in a literal race of life and death to reach American lines before the surrender deadline.

At this point, the 16th Armored Division had been halted because it had reached the Karlovy Vary – Plzen – Ceske Budejovice demarcation line. But V Corps’s other units had not reached that line. So on the morning of 7 May 1945, the 1st, 2nd and 97th Infantry Divisions and CCA 9th Armored Division resumed their advances.[48]

In the pre-dawn hours of 7 May 1945, Task Force Collins assembled its vehicles and soldiers for the drive on Karlovy Vary. At 0515, the task force began its advance and quickly passed through the positions held by Task Force Engeman. Continuing eastward, the task force encountered large groups of German soldiers who surrendered without firing a shot. Under questioning they informed their captors of the German High Command’s surrender several hours before. Just west of Falkenau, Task Force Collins turned south-east on to a secondary road and headed for the town of Hor Slavkov.[49]

At 0615, Task Force Engeman resumed its eastward attack. Like the other CCA task force, they did not encounter any German resistance. Where Task Force Collins had branched off to the south-east, Task Force Engeman continued eastward along the main road to Karlovy Vary. They passed through Falkenau, St. Sedlo and Loket (Elbegen), encountering only German soldiers eager to surrender.[50]

At 0800, V Corps Headquarters received word of the German surrender and General Eisenhower’s order to halt its forces wherever they were. With tens of thousands of soldiers advancing across a broad front, communicating the order to halt took some time to accomplish.[51]

At around 0855 Task Force Collins was passing through a swamp about 400 meters outside the village of Hor Slavko. Suddenly an order was received from Combat Command A Headquarters for them to halt their advance. “This is a hell of a place to end the war,” Lt. Col. Kenneth Collins observed to Lt. Col. George Ruhlen. Ruhlen agreed and radioed headquarters that the message was garbled and requested them to repeat it. He then turned off his radios. The two battalion commanders split up and continued eastward. After reaching Hor Slavkov and Schonfeld respectively, they re-established radio communications with Headquarters and halted their advance.[52]

Around this same time, Task Force Engeman’s lead tank commanded by Sgt. Frank M. Hendricks spotted a German motorcyclist and a truck load of soldiers. Hendricks’ crew opened fire. After the second shot, Lt. Col. Engeman pounded on the side of the tank and said, “The show’s over, Sergeant. Take it easy.” 9th Armored Division had thus fired its last combat shot at 0925. Task Force Engeman halted and consolidated its positions just outside of Karlovy Vary. Later some elements did enter the city but were withdrawn.[53]

With its advance halted, Combat Command A turned to the business of accepting and processing the surrender of the tens of thousands of German soldiers and civilians fleeing the Soviet Army. Lt. Gen. Fritz Benicke surrendered his division to the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion that afternoon. The Americans also liberated over 2,000 Allied prisoners of war from three camps west of Karlovy Vary.[54]

That afternoon, the 14th Tank Battalion was ordered to have an officer in Class A uniform with ribbons report to CCA’s Headquarters for a special assignment. Capt Cecil Roberts was the only officer in the battalion with such a uniform so he got the assignment. After arriving at CCA Headquarters, he learned why he had been summoned. He would be participating in the acceptance of the surrender of General Osterkamp and his 12th Corps. Accompanied by CCA’s Operations Officer, Major Henry Mortimer and another major from the 1st Infantry Division, Capt Roberts traveled to 12th Corps’s headquarters in Karlovy Vary. “I was a Captain but assumed the role of the senior officer because of the uniform,” Roberts later wrote in his memoirs. “We went wheeling up to the German headquarters. We were met in front by the Commanding General, his staff, and an honor guard. We went through the ritual of a formal surrender, with the General handing me his sword.”[55]

Subsequent to Capt Robert’s acceptance of the German 12th Corps’s surrender, another surrender ceremony was held with Gen Osterkamp surrendering his corps to Brigadier General George A. Taylor, the Assistant Division Commander of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division. Also present were Major Mortimer, Brig. Gen. Harrold, and several 1st Infantry Division officers. Osterkamp revealed that his corps had only about 2,200 soldiers in its three depleted divisions and that altogether there were some 17,000 Germans in his area of responsibility. There was some difference of opinion over the exact terms of the German surrender but Gen. Taylor quickly prevailed. With little choice, Osterkamp accepted Taylor’s precise terms and surrendered his corps again.[56]

VE Day 8 May 1945

Victory in Europe Day was celebrated on 8 May 1945. Celebrations, however, amongst the U.S. troops in Czechoslovakia were not as boisterous as one might expect. There still loomed the war in the Pacific Theater. Soldiers of the 2nd and 97th Infantry Divisions and several other units were scheduled to re-deploy back to the U.S. and then onto the Pacific to participate in the invasion of the Japanese Home Islands later that year. Many U.S. units held memorial services for those who had given their lives in liberating Europe and earning the victory commemorated this day. “Let all offer a humble prayer to Almighty God that He may have mercy on the souls of our gallant comrades who have paid the supreme sacrifice in our march to this glorious victory,” reflected Major General John Leonard upon this momentous day.[57]

For the soldiers of CCA 9th Armored Division and many other units in Czechoslovakia, VE-Day was a day of hard work amidst chaos. The war had ended but with it came a massive flood of surrendering German soldiers and civilians desperate to escape from the advancing Soviet armies. For the Germans, it became a literal race against time. The key time was 0001 local time on 9 May 1945. All Germans not within American lines by that time would become prisoners of the Soviets. All Germans arriving within American lines after that time would be turned over to the Soviets. The Germans all knew that Soviet captivity meant brutality and near certain death. Those Germans who beat the deadline would thus escape brutal Soviet retribution.

CCA 9th Armored Division had been halted just west of Karlovy Vary. For the several days that they were located here, thousands of German soldiers and civilians poured into their lines. Temporary holding areas were set up to handle the prisoners until they could be processed.

Two of the 9th Armored Division soldiers amidst this flood of Germans rushing west to escape the Soviets were 1st Lt Dee Paris of the 14th Tank Battalion and Private First Class Daniel Shimkus of the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion. “My tanks were placed in the forward position,” recalled 1st Lt Paris years later. “As such, we had hundreds of German soldiers surrendering, including generals. My men took their weapons and placed them in a pile in the middle of the street.” Pfc Shimkus also recalled that “some of the Germans were stragglers who threw their weapons away while others surrendered as units with their equipment. I was always amazed at how much horse-drawn equipment the Germans had.”[58]

Lt Col George Ruhlen and his 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion were also tasked with processing the surrendering German soldiers and civilians. They were located near the town of Elbogen. His men disarmed the soldiers and directed them into temporary camps on the hills surrounding the town until they could be sent back to the 1st Infantry Division and thence onto Germany. “Soon the massive numbers of Germans became nearly unmanageable. Vehicles full of Jerries were now arriving, many hitched to trailers and all overloaded with women, children, household furnishings, and junk,” Lt Col Ruhlen wrote in his history of the battalion. “The mob now consisted of some 12,000 Luftwaffe, 3000 Wehrmacht infantry, 2000 SS troops, 1000 civilians and some 2000 vehicles.” To ensure order in the camps and prevent a large-scale riot, Ruhlen placed a battery of his self-propelled guns, several attached half-tracks with quad fifty-caliber machine guns and several tanks in positions to fire directly at the camps if necessary. After several days of this difficult duty, the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion was relieved and sent back to rejoin its parent division in Germany.[59]

Hiding within this massive flood of humanity were Nazi officials and senior German commanders attempting to escape Allied justice. Numerous fleeing Nazis were able to pass through undetected. Konrad Henlein, Gauleiter and Reichsstatthalter of the Sudetenland, was not one of them. A Sudeten German, Henlein had helped instigate Adolf Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland border region of Czechoslovakia and been rewarded for his efforts by appointment to high positions within the Nazi party, the Third Reich and the SS. Around VE-Day, Henlein attempted to pass through American lines unnoticed in a crowd of German civilians. Unfortunately for the fleeing Nazi official, CCA’s commander Brig. General Thomas Harrold was at that moment inspecting the screening posts and road blocks set up by his troops. Harrold recognized Henlein in the crowd, had him arrested and turned over to U.S. Army Counter-Intelligence Corps agents. He was taken to Plzen for interrogation. While still in their custody, Henlein managed to slit his wrists using his eyeglasses and died on 10 May 1945.[60]

Throughout the spring, Allied units had been discovering and liberating Nazi concentration camps in Germany. Just a couple weeks prior, the 90th Infantry Division had liberated the Flossenbuerg Concentration Camp near the German – Czechoslovak border. On 8 May, elements of the 9th Armored and 1st Infantry Divisions liberated two sub-camps of Flossenbuerg: Zwodau and Falkenau an der Eger. The former had been established by the SS in 1944 to manufacture equipment for the Luftwaffe. Between 900 and 1,000 starving female prisoners were liberated at Zwodau and another 60 prisoners were liberated at Falkenau.[61]

Within a day or two after VE-Day, the Soviet Army arrived at Karlovy Vary and the U.S. soldiers made contact with them. On the night of 11 May 1945, a large formal party was held at the Richmond Park Hotel in Karlovy Vary that included U.S. soldiers, Soviet soldiers and representatives of the Czechoslovak Government. Capt Cecil Roberts of the 14th Tank Battalion was one of the U.S. soldiers who attended the party. “The Russians were our allies on 11 May 1945,” recalled Capt Roberts “We were all happy, drinking vodka and celebrating at the time. The problems began sometime later during the occupation.”[62

Occupation and Return Home

At 0001 local time on 9 May 1945, the Second World War in Europe officially ended. Third U.S. Army forces in western Czechoslovakia had some time to celebrate with the newly liberated Czech people but disarming and accepting the surrender of the remaining German forces took precedence. Now as an Army of Occupation, Third U.S. Army engaged in processing German prisoners of war, repatriating liberated Allied prisoners of war and civilian refugees, maintaining order in the liberated areas and assisting the Czechs with re-building their country. XII Corps and most of V Corps left Czechoslovakia by the end of May 1945. U.S. forces remained in Czechoslovakia under the command of XXII Corps until December 1945 to help the Czechs.[63]

CCA 9th Armored Division was relieved by other American units on 12 May 1945 and returned to Germany to rejoin their parent division. The 9th Armored Division served on occupation duties in Germany throughout the summer of 1945. On 2 October 1945, the division embarked on ships and set sail for the United States. The division’s members arrived at New York and Boston on 10 October. Three days later, the 9th Armored Division was officially deactivated at Camp Patrick Henry, near Newport News, Virginia.[64]

Conclusion

In just three short years, the 9th Armored Division amassed an impressive record of combat service during World War Two. Formed from horse cavalry units, the soldiers of the 9th Armored employed modern armored vehicles to help in the liberation of western Europe and the defeat of the Third Reich. The division started the European Campaign on the defensive in the Ardennes region, but after the December 1944 German counter-offensive was decisively defeated the 9th Armored Division took part in the irresistible Allied drives which overran Germany. When World War Two in Europe finally came to a close on 7 May 1945, the division’s Combat Command A was attacking eastward to liberate northwestern Czechoslovakia --- one of the last Allied units still advancing when the German High Command surrendered.

*The author served as a Religious Program Specialist in the U.S. Navy Reserve for eight years, mobilizing and deploying twice to Iraq for Operation Iraqi Freedom. He served with the U.S. Marines MWSS-472 from January 2008 until June 2011 and served as Assistant Squadron Historian in 2009 and Squadron Historian in 2010/2011 as a collateral duty. He was honorably discharged in June 2011 as a Religious Program Specialist First Class (Fleet Marine Force).

[1] Robert S. Cameron, Mobility, Shock, and Firepower: The Emergence of the U.S. Army’s Armor Branch, 1917 – 1945. (Washington DC: Center of Military History, 2008). See Chapter 13 specifically.; Robert R. Palmer, “Reorganization of Ground Troops for Combat.” Found on pages 261-384 of Kent Roberts Greenfield, Robert R. Palmer and Bell I. Wiley’s The Army Ground Forces: The Organization of Ground Combat Troops. In the series The United States Army in World War II. (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1987). See Part V specifically for the armored forces reorganization.; Mary Lee Stubbs and Stanley Russell Connor. Army Lineage Series Armor-Cavalry Part 1. (Washington DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1969), pp. 58-63.; George Forty, United States Tanks of World War II In Action. (NY: Blandford P, 1983), pp. 22-28.; George Forty, U.S. Army Handbook 1939-1945. (NY: Barnes & Noble Books, 1995), pp. 79-86.

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid.

[4] U.S. Army. U.S. Army European Theater of Operations. Office of the Theater Historian. Order of Battle of the United States Army World War II: European Theater of Operations. Paris, France: December 1945. pp. 498-505. [Hereafter cited as US Army ETO Order of Battle.]; See Chapter 1 of Dr. Walter E. Reichelt’s Phantom Nine: The 9th Armored (Remagen) Division, 1942-1945. (Austin, TX: Presidial P, 1987.). Dr. Reichelt served in the 52nd Armored Infantry Battalion.

[5] See Chapter 1 of Phantom Nine.

[6] Biographical materials on Col. Engeman provided by Lt Colonel Dee Paris, USA (Ret.) of 14th Tank Battalion Association.

[7] Demetri "Dee" Paris, Lt. Colonel, USA (Ret.). 1st Lieutenant. Platoon Leader. D Company / 14th Tank Battalion / Combat Command A / 9th Armored Division. Letter to the Author. 10 November 1999.; Cecil Roberts. Colonel, USA (dec.). Captain. S-3 (Operations) Officer. 14th Tank Battalion / Combat Command A / 9th Armored Division. A Soldier From Texas. (Fort Worth, TX: Branch-Smith, Inc., 1978).

[8] George Ruhlen. Major General, USA (dec.). Lt. Colonel. Battalion Commander. 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion / Combat Command A / 9th Armored Division. Letters to the Author. 31 May 1998 and 1 November 1999.

[9] Reichelt, pp. 18-22.

[10] Ibid.

[11] For a more detailed discussion of the European Campaign, I recommend the following: Stephen E. Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers: The U.S. Army from the Normandy Beach to the Bulge to the Surrender of Germany. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997); Charles B. MacDonald, The Mighty Endeavor. (New York: Da Capo P, 1969). Russell F. Weigley, Eisenhower’s Lieutenants: The Campaign of France and Germany 1944-1945. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana U P, 1981); and the U.S. Army’s official histories of World War Two, published as the series The United States Army in World War Two.

[12] US Army ETO Order of Battle, pp. 498-505.; See Chapters 2 and 3 of Phantom Nine.

[13] Dr. Reichelt’s Phantom Nine details the 9th Armored Division’s operations during the Battle of the Bulge.

[14] See Chapters 7, 8, and 9 of Phantom Nine.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] U.S. Army. Third U.S. Army. After Action Report. 3 vols. U.S. Army Military History Institute Archives. Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. [Hereafter the After Action Report is cited as TUSA AAR.] [Hereafter the Archives is cited as USAMHI Archives.]; Charles M. Province, Patton’s Third Army: A Chronology of the Third Army Advance August, 1944 to May, 1945. (NY: Hippocrene Books, 1992).

[18] Ibid.; A note on geographical names. Because western Czechoslovakia (Bohemia) was historically settled by both Czechs and Germans, many towns in this area have both German and Czech names and spellings. Thus the city of Cheb is known as Eger in German. In this article, the Czech name/spelling will be used primarily.

[19] Ibid.

[20] U.S. Army. V Corps. Operations in ETO 6 January 1942 to 9 May 1945. (Germany: 1945), USAMHI Library. [Hereafter cited as V Corps in ETO.]; The First: A Brief History of the 1st Infantry Division, World War II. (Privately published by the Cantigny First Division Foundation, 1996), pp. 10-11.; U.S. Army. 102nd Cavalry Group. 38th Cavalry Squadron. After Action Report 1 - 31 May 1945. USAMHI Library. [Hereafter cited as 38th Cav AAR].;The History of the 17th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, (Seattle, WA: Lowman & Hanford Co., 1946?)

[21] US Army Order of Battle, pp. 498-501.

[22] Col. Cecil Roberts, Letter to the Author, 28 June 1998.

[23] Paul M. Crucq, Strike, Fight, and Conquer: The History of the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion in World War II July 1942 - October 1945. (Drukkerij Truijen, Rijswijk: 1993), p. 381. My thanks to Robert Ellis of the battalion for providing me with photo-copies.; Chapter Nine of Phantom Nine.

[24] TUSA AAR.; Freiherr von Gersdorff, “The Final Phase of the War: From the Rhine to the Czech Border,” draft trans. from the German. (Oberursel, Germany: U.S. Army, Europe - Historical Division [Foreign Military Studies Branch,] March 1946).; Rudolf Toussaint. "Military Area Prague." Karlsruhe, Germany: US Army, Europe – Historical Division [Foreign Military Studies Branch], written sometime between 1945 & 1954. Copy located at US Army Military History Institute.; Karl Weissenberger, “Battle Sector XIII (Wehrkreis XIII) (May 1945),” (Karlsruhe, Germany: U.S. Army, Europe - Historical Division [Foreign Military Studies Branch,] 1946). After the war, US Army historians interviewed hundreds of captured German officers. These historical reports are now kept at the U.S. Army Military History Institute and the National Archives.; Lt. Col. George Dyer, XII Corps: Spearhead of Patton’s Third Army, (privately published by the XII Corps Historical Assocation, 1947), pp. 424-6;

[25] Dyer, pp. 424-6; U.S. Army. Third U.S. Army. XII Corps. 90th Infantry Division. After Action Report - Month of May 1945. Record Group (RG) 407. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). Archives II – College Park, Maryland.

[26] U.S. Army. 9th Armored Division. Combat Command A. After Action Report for 1 - 8 May 1945. Germany: 1 June 1945. [Hereafter cited as 9AD CCA AAR.]. My thanks to Gen. Ruhlen for sending me a copy of this AAR.; Chapter Nine of Phantom Nine.

[27] Ibid.; U.S. Army. 9th Armored Division. Combat Command A. 60th Armored Infantry Battalion. After Action Report for 1 - 8 May 1945. Germany: 28 May 1945. [Hereafter cited as 60AIB AAR].; U.S. Army. 9th Armored Division. Combat Command A. 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. After Action Report for 1 - 8 May 1945. Germany: late May 1945. [Hereafter cited as 3AFA AAR.]; U.S. Army. 9th Armored Division. Combat Command A. 14th Tank Battalion. After Action Report for 1 - 8 May 1945. Germany: late May 1945. [Hereafter cited as 14th Tank AAR.] My thanks to Gen. Ruhlen for copies of these after action reports.; Chapter Nine of Phantom Nine.

[28] 9AD CCA AAR, pp. 2-3.; Crucq, p. 381.; Chapter Nine of Phantom Nine.

[29] Crucq, p. 381.; 9AD CCA AAR, pp. 2-4.; 14th Tank AAR; 60AIB AAR, p. 2.

[30] See V Corps in ETO.

[31] Crucq, p. 381.; 60AIB AAR, p. 2.; 14th Tank AAR.; Chapter Nine of Phantom Nine.

[32] Crucq, p. 381.; 60AIB AAR, p. 2.

[33] Major Gen. George Ruhlen. History of the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. 2nd ed. (San Antonio, TX: privately published in 1986), p. 143. [Hereafter cited as History of 3rd AFAB.] My thanks to MGEN Ruhlen for sending me excerpts of his history.

[34] U.S. Army. 1st Infantry Division. Letter of Instructions - 041100 May 1945. re-printed in 9AD CCA AAR, pp. 4-5.

[35] The emergence of the U.S. / Soviet Cold War as demonstrated by the military and diplomatic events in Czechoslovakia in 1945 was the subject of the author’s Masters Thesis. Bryan J. Dickerson, “Czechoslovakia 1945: Prelude to the Coming U.S. / Soviet Cold War.” (Masters Thesis, Monmouth University, 1999).; See also Forrest C. Pogue’s “The Decision to Halt at the Elbe.” Command Decisions. ed. by Kent Roberts Greenfield. (NY: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1959), pp. 374-387. ;

[36] “SCAF (Supreme Commander Allied Forces) to Bradley [12th Army Group] and 9th Air Force Commanding General 4 May 1945.” SCAF Cable No. 335. Found in Nevins, Arthur S. Brigadier General, USA. Chief of

Operations Planning Section. Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force. G-3 (Operations) Division. Personal Papers. USAMHI Archives.;

[37] TUSA AAR, pp. 392.; V Corps in ETO, pp. 450.; Hobart Gay, Major General, USA. Chief of Staff. Third U.S. Army. Diary. Personal Papers. USAMHI Archives, p.919.; U.S. Army. Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). Message from Eisenhower to Bradley - Ref No. FWD-20726 6 May 1945. Outgoing Message File. RG407. NARA.; U.S. Army. Twelfth U.S. Army Group. Letter of Instructions No. 22 - 4 May 1945. RG407. NARA.

[38] Ibid.

[39] TUSA AAR.

[40] See the Third U.S. Army After Action Report, V Corps in ETO, and LtCol Dyer’s history of XII Corps for more details.

[41] This account of Combat Command A’s operations is compiled from the following sources: Major General George Ruhlen, USA (dec.). Lt. Col. Battalion Commander / 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. Letters to the Author of 19 May, 31 May and 4 August 1998, and his History of the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion.; and Col. Cecil Roberts, A Soldier From Texas; Lt. Col. Demetri Paris, USA (Ret.). 1st Lt. Platoon Leader. D Company / 14th Tank Battalion. Letters to the Author of 31 May, 4 June, 17 June, and 25 June 1998.; Col. Leonard Engeman, USA (dec.). Lt. Col. Battalion Commander. 14th Tank Battalion. “Col. Engeman Remembers Czechoslovakia.” Copy provided by LTC. Paris.; Paul M. Crucq’s Strike, Fight and Conquer: The History of the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion in World War II July 1942 - October 1945.; Dr. Walter Reichelt’s Phantom Nine; Col. Daniel Shimkus, USA (dec.). Private. Armored Infantryman. 60th Armored Infantry Battalion. Phone Interview by Author. 11 May 1998.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.; Lt Col Paris. Letter to the Author. 15 December 1999

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] John MacCormac, “Czech Patriots Take Prague, Then Beg Aid as Foe Attacks,” New York Times. 6 May 1945: 1+.; U.S. Army. SHAEF. Outgoing Message File. Message from Eisenhower to US Military Mission, Moscow - 8 May 1945 (Ref. No. FWD-21001).” RG407, NARA.; U.S. Army. SHAEF. Outgoing Message File. Message from Eisenhower to US Military Mission, Moscow - 8 May 1945 (Ref. No. FWD-21006).” RG407, NARA.

[48] See V Corps in ETO.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid.

[51] V Corps in ETO.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Roberts, pp. 79-81.

[56] CCA, 9th Armored Division AAR, pp. 13-4. The full account of Osterkamp’s surrender runs four pages and contains Taylor’s precise instructions for how Osterkamp was to surrender his forces.; Major Henry T. Mortimer, S-3 (Operations) Officer. Combat Command A / 9th Armored Division. Letter to Col. Cecil Roberts - 27 August 1987. Copy provided to the Author by Col. Roberts.; See also Chapter Nine of Phantom Nine.

[57] U.S. Army. 9th Armored Division. Headquarters. General Orders Number 81 - 9 May 1945. RG 407. NARA.

[58] Lt. Col. Dee Paris. Letter to the Author - 25 June 1998.; Col. Daniel F. Shimkus, USAR (dec.). Private First Class. Rifleman. 1st Platoon / Company B / 60th Armored Infantry Battalion / Combat Command A / 9th Armored Division. Letter to the Author – 18 April 1998.

[59] Ruhlen, 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion History, pp.145-7.

[60] CCA 9th AD AAR.; Reichelt, pp. 280-282.

[61] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The 9th Armored Division.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10006146 Accessed on 7 March 2013.

[62] Col. Cecil Roberts, Letter to the Author - 28 June 1998.; Roberts, A Soldier From Texas, p. 81.

[63] See Chapter 9 of Phantom Nine.

[64] Ibid.

Comments

Discovery near Goslar 26 April 1945

I understand a German nuclear device was captured near Goslar on 26 April 1945 by the Ninth US Army. Please can you shed some light on this discovery?

Famly search

Look for any one who might remmber Sgt Clarence D Edwards 9th armor Division killed march 15 1945 Kalenborn germany Thank you

liberation of Polish officer camp(s)

I wonder if there is an account(s) of a American soldier that describes action at Warburg, Germany and personal impressions of the liberation of Polish officer camp(s). My grandfather had been a POW at Oflag VIB in Doessel, Germany for 5 and 1/2 years. His camp was liberated on April 1, 1945 (Easter Sunday that year) by the 9th Armored Division.

I am writing a book, and missing is the perspective of an American soldier who may have been a part of the liberation.

89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron CCA

Firstly thanks for the excellent work presented. My father Leon Levin was a scout in the 89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, I believe Troop C. I am trying to document his stories for my children and future generations. Your work will certainly help.

Post new comment