U-Boats in the Arctic: An Expensive German Mistake

The Nazi war against the Soviet Union defined the Second World War's outcome. Had the Germans focused single-mindedly on fighting that war (following their unprovoked June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union code-named Operation Barbarossa) the world may look very different today. Thankfully, they did not. In fact, during the war's critical years of 1941-1942 the Mediterranean theater would prove to be the biggest drain on the German war effort. Nonetheless, and somewhat paradoxically, another problematic distraction would prove to be the naval battles in the frigid Arctic Ocean.

During the initial months of Barbarossa the German Navy (Kriegsmarine) redeployed into active duty within the Baltic Sea five coastal Type II U-boats. These U-boats, having been relegated to training status earlier in the war, in and of themselves hardly represented a drain on German resources. Armed with only five torpedoes and relatively short ranged, even the well built Type IID model was hardly suitable for patrolling the vast North Atlantic that represented the linchpin of the German naval effort. A naval effort that at that time was only belatedly ramping up.

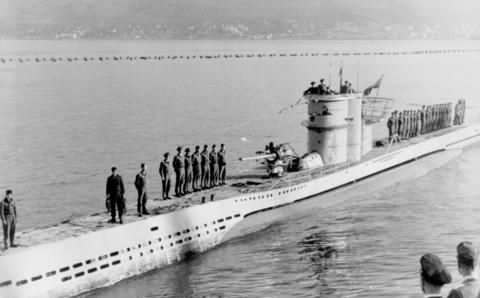

In June of 1941 the Kriegsmarine deployed a mere 38 U-boats (mostly the Type VIIC U-boats that served as the workhorse deep water U-boat - with U-251 pictured here in Narvik Norway during July of 1942) actively patrolling the open ocean. Though the U-boat fleet stood at 150 vessels at that time, the majority were in training or undergoing sea trials after production accelerated following the onset of continent wide warfare. However, the Type II U-boats were more than adequate for operations in the Baltic's tight waters. There, and during Barbarossa's initial months they helped a motley group of small naval craft and at times substantial air assets, to hem into port the large but poorly trained and led Soviet Baltic Fleet. However, the Baltic Sea was only part of the story when it came to naval operations on Barbarossa's northern flank.

Over six hundred miles to the north the Soviet Union's Arctic coastline had become a significant battleground. The Arctic Ocean is an incredibly difficult place to conduct military operations. Floating pack ice threatens naval vessels and merchant ships alike. During the summer the sun shone for 24 hours, providing scant opportunity for U-boats to operate without being spotted in the shallower waters near the most important part of the Soviet Arctic coastline - the Kola Peninsula and it's port of Murmansk. There, a seventy mile wide stretch of sea stayed ice free year round. However, in addition to the problems posed by perpetual daylight, perpetual darkness from November to January also made the U-boats job hardly any easier. That's because Second World War submarines were really submersibles that spent much of their time surfaced. Without the assistance of other reconnaissance assets like aircraft the U-boats job of locating targets was that much more difficult. In addition, the barren, rugged coastline made it easy for Soviet convoys to shelter in the safety of the littoral. There Type VIIC U-boats struggled to remain concealed or even launch torpedoes that all too often bottomed out in the shallow water.

Nevertheless, as part of Barbarossa the Germans had decided the port of Murmansk and the important Finnish Petsamo nickel mines would be attacked. To that end the German Alpine Corps Norway, XXXVI Mountain Corps (Gebirgskorps) and Finnish III Corps attacked Soviet positions near the German lines in Norway - hoping to advance the roughly 75 miles to Murmansk in just over a week and seize the Russian port by the end of June 1941. This northern army totalled six divisions of well-trained soldiers. In addition the Luftwaffe provided 60 combat aircraft in support. Furthermore, the Germans had seen fit to attach approximately 250 tanks to this force - in the form of Panzer-Abteilung 211's 170 captured French tanks as well as Panzer-Abteilung 40's smaller complement of German manufactured tanks. This represented a sizeable commitment of Axis resources at a time when the Wehrmacht's main body needed every man and tank they could get further south on the road to the strategically more significant targets of Leningrad, Moscow, and the absolutely vital Caucasian oil fields.

The Finnish and German command attacked into the Kola Peninsula, quickly capturing the Petsamo mines. However, soon after the offensive ground to a halt in the face of dogged Soviet resistance that included the Red Banner Northern Fleet's capable support of it's brothers in arms on land. There the Axis army would remain locked in trench warfare well short of Murmansk, until finally driven back into Norway in 1944. As early as July of 1941 it was glaringly obvious that any attempt to take Murmansk would require a greater commitment of air and land assets that would not be forthcoming due to the demands the German Eastern Front placed on Army Group's North, Center, and South. In spite of this reality the German high command elected to double down on failure in a manner that couldn't possibly change circumstances on the ground. To that end they redeployed four Type VIIC U-boats from better use in the North Atlantic and into the Arctic Sea - ostensibly to intercept Soviet shipping and stop a repeat of a surprising Soviet amphibious assault behind German lines on the Kola Peninsula.

At the same time, the United States and Great Britain had extended Lend-Lease aid to the Soviet Union. The port of Murmansk would prove to be one of three key destinations for this aid; in this case ships sailing from the U.S. and British Isles. During the Second World War Murmansk received nearly one quarter of Allied Lend-Lease aid delivered to the Soviet Union. The first test convoy of six merchant ships reaching the Soviet Union from Great Britain on August 31, 1941 (arriving in Archangelsk). In addition, just over a quarter of Allied Lend-Lease aid reached the Soviet Union via Persia (beginning in mid-1942) while the bulk of the aid crossed the Pacific and entered the Soviet Union at the port of Vladivostock - half of all wartime deliveries (also beginning in the middle of 1942).

Meanwhile in the Arctic Sea and late in September 1941 the first of the large PQ convoys left Great Britain for the Soviet Union. Ostensibly this demanded the Germans respond. They could ill afford to have tanks, aircraft, and other such war material steaming unmolested into Soviet harbors to replenish the Red Army when it was very much on the ropes. However, much as in other cases the manner in which the Germans sought to interdict this aid proved problematic. These decisions, made far from the battlefield, would have an enormous impact on the war's course.

November of 1941 is not often thought of as a critical month during the Second World War in comparison to say December of the same year. However, it would prove vital to the shape of the German war against the Soviet Union. That's because on November 13th an OKH conference at Orsha fatefully decided the final plans to take Moscow. There the decisions made by the German Army's high command pushed an overextended Ostheer into the ground at a time when it held not just qualitative superiority over the Red Army but quantitative in several key weapons (particularly in terms of AFV's).

At the same time Hitler conferenced at the Wolfsschanze with senior officers of the Kriegsmarine. This time it would be Hitler's turn to make the wrong decision. The German Navy's officers argued against further U-boat deployments in the Arctic Ocean. They cited to the horrible winter weather, unique navigational problems presented by the underwater topography, and of course conditions hardly conducive to spotting and sinking Allied shipping. As it was, patrolling U-boats were spending weeks at sea without accomplishing anything of significance. All but one of the 48 ships in the initial PQ convoys made it to Soviet ports late in 1941 - with the one ship damaged by ice and not U-boats. Meanwhile, Germany's U-boats in the North Atlantic were regularly sinking Allied shipping during what was known as the U-boat crews "happy time" of the war. Moreover, the burdens of fighting in the Arctic meant that to even maintain three U-boats on patrol the Germans would need to take nine from the North Atlantic (under the standard formula of three boats on station, three in transit, and three in maintenance or training).

However, in spite of all of that Hitler became increasingly fixated on redeploying significant German naval assets to the Arctic. Not only to protect Norway from an anticipated Allied invasion (given reports in December of 1941 to that effect gathered by German intelligence from credible sources), but to interdict the Allied PQ convoys to Murmansk. This decision-making proved disastrous. Not least of all because following Germany's declaration of war on the United States the German Navy had allocated five long range Type IX U-boats to wage war along the Eastern U.S. seaboard (Operation Paukenschlag) with more scheduled to follow into the same area and for conducting follow-up strikes targeted in the Caribbean.

However, the Germans only had 91 operational U-boats in total during December of 1941, with limited numbers of long-range Type IX U-boats. Thus Type VIIC U-boats also participated in these operations. To say that this initial effort caught the Americans flat footed was an understatement. In just two months these few U-boats sank 87 ships totalling over a half million tons of shipping in a disaster greater than that of Pearl Harbor. In Britain, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, in a March 12, 1942, cable sent to Harry Hopkins, President Roosevelt’s aide, wrote, “I am most deeply concerned at the immense sinking of tankers west of the 40th meridian and in the Caribbean Sea. … The situation is so serious that drastic action of some kind is necessary.” As the few U-boats in the Western Atlantic slaughtered Allied shipping at unprecedented rates, Hitler and the German Navy raised the numbers of U-boats in the Arctic Sea - from four in January of 1942 to twenty-one in March.

One could only imagine what an additional seventeen U-boats would have accomplished in the Western Atlantic during that same time period. Remember this was a time when American overseas operations faced considerable strain due to a global shipping crunch - particularly in oil tankers. As it was the Liberty Ship program was still ramping up early in 1942 (the first Liberty Ships had been launched in September 1941), and it is not a stretch to argue that doubling the number of U-boats off American shores early in 1942 may have impacted the gathering of enough shipping to conduct Operation Torch (the Allied invasion of Northwest Africa) and delayed it from November of 1942 into January of 1943. Or Torch might have been called off all-together as the Allies concentrated on building up forces in England, therefore granting Axis forces a much needed respite in the Mediterranean - and allowing them to concentrate greater force in Eastern Europe at the worst possible time for a Soviet war machine picking itself up off the floor late in 1942.

Now, one could argue that these additional Arctic deployed U-boats weren't useless, and that is true. Overcoming deplorable operating conditions in the frigid Arctic Sea (where ice imposed massive costs in terms of wear and tear on men and machines alike) the Arctic U-boats played a pivotal role in bringing the Allied Lend-Lease PQ convoys to a halt in 1942. But again this didn't really begin to happen until the spring of 1942. It bears repeating that as late as February of 1942 the Arctic U-boats were sinking next to nothing while an equal number of their peers in the Western Atlantic were sending half a million tons of Allied shipping to the ocean floor.

Nevertheless, in March of 1942 the Arctic U-boat fleet of nearly two dozen vessels, or almost one fifth the German Navy's operational strength in U-boats, began impacting the PQ convoy's in an appreciable way. However, this effort wasn't occuring in a vacuum. To support the anti-shipping effort the Luftwaffe had redirected a considerable air fleet into Norway including 103 Ju88 bombers, 42 He-111 bombers, 14 He-115 bombers, 30 Ju-87 dive bombers, and nearly 75 reconnaisance aircraft including 30 Fw200 and Ju88 aircraft otherwise in high demand over the North Atlantic. To put the size of this air force in perspective, on the southern sector of Germany's Eastern Front the availability of the 8th Air Corps (Fleigerkorps VIII) played a key role in the German ability to conduct offensive operations in the Crimea and near Kharkov with Fleigerkorps VIII switched back and forth between the two during the spring of 1942. Again, one can only imagine how much worse things would have been for the Red Army at that time had the substantial air power gathered in Norway been used not only over the eastern Ukraine and southern Russia but also the Black Sea.

Meanwile, on June 27, 1942 the PQ convoy battles reached their apex when PQ-17's thirty-four mechantmen and a strong escort of surface ships and submarines departed Hvalfjord, Iceland bound for Murmansk. The Germans had gathered ten U-boats, the air fleet in Norway, and also put on notice the strongest remnants of the German surface fleet (then located in Norway) - The battleship Tirpitz, pocket battleships Admiral Scheer and Lutzow, heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, along with a strong destroyer escort.

The battle for PQ-17 went disastrously for the Allies. On July 4th the threat of the German surface fleet, which had sailed, scattered the convoy and it's escorts. The U-boats and Luftwaffe swept in for the kill. By July 13th the eleven surviving of thirty-four merchant ships that had left Iceland reached the Soviet Union. U-boats sank sixteen of the merchant ships, the Luftwaffe took the rest. In turn the Germans lost only five aircraft. Not a single U-boat was sunk. The disaster prompted the Allies to call off the PQ convoys and close down until September the northern supply route into Russia. As bad as it was for the Allies however, it could have been worse.

That's because, in the Western Atlantic and in May alone, the Allies lost 115 merchant ships off the American coast, with more than half sunk in the Gulf of Mexico. This distressing figure rose to 122 ships sunk in June, representing over one million tons of shipping in May and June, or half of what the Allies had lost during the entirety of 1941. Oil tanker losses were so severe that they threatened to undermine the U.S. ability to project power overseas. Now, my readers know I am firmly convinced the war between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union decided the Second World War. So they might be saying, wait a second, wasn't the German Navy doing exactly what this author would have wanted in concentrating its efforts in the Arctic? Not at all, and this is why.

Not only does the spring-summer of 1942 carnage in the Western Atlantic reinforce the importance of the German Navy scrapping up every U-boat it could find and sending it to the Caribbean and U.S. Eastern Seaboard, but one must remember something else as well. Of the sixteen merchant ships sunk by U-boats in the epic PQ-17 convoy battle (a battle that ranked as the Axis high-point of the naval war in the Arctic) - fourteen were American. Ships such as the 5,000 ton merchantman Carlton loaded up with nineteen tanks, and hundreds of tons of munitions in the port of Philadelphia during March of 1942 and lost as part of PQ-17 early in July. A ship that could have far more easily been intercepted by any one of the expensively supported U-boats sailing the inhospitable Arctic Ocean had they been redeployed into the Western Atlantic.

Thus, the same war material going to replensh Germany's mortal enemy and ultimate nemesis just as easily could have been intercepted and destroyed along with who-knows-how-many-other ships by those same U-boats had they been deployed into the huge window of opportunity represented by the rich Atlantic and Caribbean hunting grounds. Regardless, this window of opportunity was already closing as the summer of 1942 ended. Thus, the Germans, who had all the resources they would have needed to secure their hegemony over Europe in 1941-1942, instead whittled away those same resources in strategic cul-de-sacs like the Arctic Ocean - this done at a time when a concentrated effort in the war's most important theaters of operation might have secured a very different outcome to the Second World War.

Post new comment