Kasserine Pass - February 1943

The Battle for Kasserine Pass represents one of the worst American military performances in the twentieth century. That said, as bad as the Battle for Kasserine Pass went it could have been a lot worse. Instead, and saving the Allies from a more significant defeat, the Germans undermined their own chances to create a significant operational and even strategic level success because, in part, and as was all too common during the Second World War, they failed to create a unified command with clearly defined and agreed upon objectives. In this instance part of the problem was that German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and General Hans von Arnim held a deep-seated animosity toward each other. Most critically, during the planning for the February 1943 German counteroffensive in North Africa they failed to come to agreement on even basic aspects undergirding the plan. Tactical and operational level German command mistakes would cause the Axis to miss out on a golden opportunity to deal the Allied armies in Tunisia a sharp and potentially severe blow.

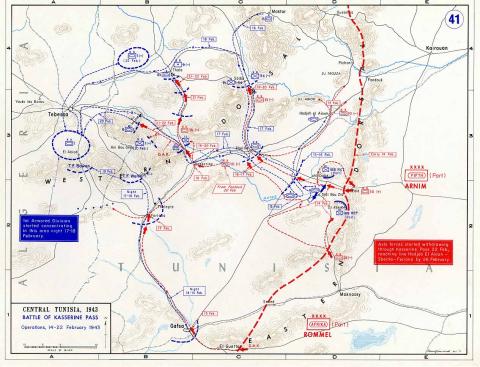

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring brought the two officers together on February 9, 1943 and together the three hammered out a plan for attacking the Allied forces that had landed in Algeria and Morocco during November of 1942 and then driven east into Tunisia. The plans called for Arnim to attack into western Tunisia with the 10th and 21st Panzer Divisions, earlier loaned to him by Rommel, and penetrate the Faid Pass as part of a northern axis of advance. Rommel's spearhead, led by a battle group from Afrika Corps, would advance from the south to take Gafsa. Units from Arnim's command, turned over to Rommel once Arnim had accomplished his immediate goals, would then supplement Rommel's force and a drive deep behind allied lines. It was from this prism which Rommel viewed the counteroffensive - as a chance to advance deep into the Allied rear in central Tunisia. There was little doubt the Allied army had overextended itself when it pushed into northeast Tunisia. Thus, Rommel sought to take advantage of the spread out Allied armies and hamstring them logistically, as well as improving the Axis army's own shaky logistical standing, by seizing the huge allied supply dumps at Tebessa. From Tebessa the German army would be in position, at only 100 miles from the coast, to threaten the entire Allied armies with encirclement by driving north to the coast; forcing the allies to withdraw or face annihilation. Then Rommel could pivot to the east and with the strength of the combined German armies turn on Montgomery, where he sat before the Mareth line in southern Tunisia. Arnim however remained fearful of such a bold plan and sought a more limited attack. The failure to iron out the differences between these two commanders later worked against the German attempt to achieve a decisive victory.

Opposing Arnim and Rommel was American General Fredendall, commanding the American II Corps. Fredendall was the perfect opponent for Rommel as Fredendall was anything but an aggressive leader who had woefully deployed his troops in isolated outposts on the heights of key passes but with almost no concentrated reserves ready to react to an immediate threat on short notice. Fredendall's main force, the US 1st Armored Division's Combat Command A and Combat Command C sat isolated in the German path. Combat Command A loosely defended the Faid Pass and the important Sidi-Bou-Zid Road - the primary communications artery running through the region. Fredendall split CCA between widely separated djebels (hills) bracketing the Sidi-Bou-Zid Road, placing only one tank battalion and a reconnaissance battalion in reserve to the rear. With mutual support for the defensive positions almost non-existent, the Germans had the chance to isolate and defeat the Americans in detail. That is not to say an American combat command was anything to sneeze at; it roughly equaled a brigade in size (CCA represented one-third the 1st Armored Division's striking power). In some respects similar to a German kampfgruppe, the American combat command was nonetheless a more limited formation as it was formed from a single armored division; it soon proved not as flexible as the German combined arms teams which were often more informally created and tailored to specific missions.

If the Germans destroyed the American positions near Faid, German forces would be in position to take the key road junction at Sbeitla; 35 miles to Faid's west. The two roads running west and north from Sbeitla offered Rommel a chance to penetrate the formidable Western Dorsal Mountains in central Tunisia and would allow for a quick push on Kasserine and then Tebessa to the west, or support a move north to Sbiba. Such a maneuver would force the Allies to attempt to defend in two directions, and thus would allow Rommel the freedom to choose where to concentrate for the decisive blow. Rommel wanted the 10th Panzer Division and a detachment of Tiger tanks to reinforce his units for the primary push. Arnim refused however, and Rommel made do with a second small force that he ordered to take Gafsa, far to Arnim's southwest.

The German assault began on Sunday February 14, 1943. A heavy sandstorm had covered German pioneers who cleared paths in the American mine fields and offered Lieutenant General Heinz Ziegler and the men in the 10th Panzer Division even more of an advantage over the inexperienced Americans. Not that Ziegler needed the help. Ziegler was an experienced combat officer with an impressive combat resume, including service on the Russian front. The 10th Panzer began the offensive near Faid by skipping past the American 168th Regimental Combat Team and then pounding into the American Combat Command A (CCA). The Germans swarmed the Americans; launching attacks both frontally and from the flanks. Although the American reserve battalions launched a brave counterattack, CCA disintegrated under the German pressure. Some units put up a stiff fight but many GIs fled the battlefield in panic - leaving considerable amounts of equipment behind. By the day's end, one-third the 1st Armored Division's striking power had melted away, with 1,500 men and well over 100 tanks and other armored vehicles lost. The German troops took Gafsa the following day and swiftly began their move on Kasserine as the remaining elements from the 1st Armored Division moved to intercept the German advance near the Faid pass.

The 1st Armored Division's reinforced CCC had received orders to punch through to the cut-off American troops; however, the American counterattack quickly ran into trouble. German Stuka's broke up the attacking forces as they sat in their assembly areas. Long-range fire from German artillery and anti-tank guns picked apart American frontal assaults moving nakedly across the open land. On top of that, the Germans promptly and aggressively counterattacked. Again, a wave of American troops fled in panic, with one American armored battalion completely annihilated. The German quickly cut-off the Americans and marched many off to prisoner of war camps. In just two days, the Americans lost over 3,000 soldiers and the equivalent of half an armored division.

British Lieutenant General Kenneth Anderson, Fredendall's commanding officer and a man equally responsible for the initially poor allied dispositions, attempted to withdraw his exposed army in response to the carnage at the front. Arnim meanwhile moved reconnaissance units forward to Sbeitla. Arnim's moves created a renewed panic amongst the Americans, who again fled in disorganized confusion. Further south Rommel's small force, advancing from Gafsa, scattered the American forces it encountered and captured the airfield at Thelepte, where the Americans abandoned and destroyed 30 of their own aircraft on the ground because of Rommel's speedy advance. Rommel was ready to go for broke, and sought a deep move into the American rear designed to not just eviscerate Anderson's army but also take apart the entire allied front in Tunisia. Nevertheless, Arnim exasperatingly refused to agree to such a plan, and only consented to a reconnaissance in force near Sbeitla. Rommel could not convince Arnim to timely release to him the 10th Panzer Division and Rommel's old 21st Panzer Division - divisions critical to exploiting the initial German penetrations. Rommel appealed to Kesselring repeatedly for help, and communications between the two flowed back and forth on February 16th. Meanwhile Kesselring met with Hitler in Rastenburg but it was too late; the decisive moment passed as the fractured and halting German command provided the Americans breathing space.

Though further German assaults met increasing resistance had the Germans made a concentrated effort in a timely fashion the Allies may have been in deep trouble. Rommel rushed ahead anyway with weaker forces, and the Americans duly stopped his frontal attacks at Kasserine Pass and Sbiba. All the same, follow up German attacks on Kasserine with stronger forces broke through, and by the day's end on the 20th Rommel had seized Kasserine Pass. Allied reinforcements however, blocked Rommel's attempts to move further forward. Rommel mistakenly exacerbated the German loss in initiative when he split his command. Accordingly, the American 1st and 34th Divisions, well supported by artillery, stopped the 21st Panzer Division cold on the road to Le Kef. Meanwhile 20 miles west of Kasserine Pass the Americans also checked the 10th Panzer Division's advance. Well dug in American infantry, again heavily supported by artillery, this time located on the high ground at Djebel el Hamra stopped the Germans in fierce fighting. The American 27th Field Artillery Battalion alone fired over 2,000 rounds in support of the beleaguered American infantry. Although the American infantry faltered, they held and then drove back the seemingly invincible German panzer grenadiers. At the same time, on February 21st the 10th Panzer's remaining units met a wall formed by British infantry supported by 50 tanks of questionable quality, but backed up by American artillery led by Brigadier General Stafford Le Roy Irwin of the 9th Infantry Division. Irwin aggressively rained harassing fire down on the assembling panzers and a group of British tanks sallied forth in an abortive counterattack that although resulting in 7 of 10 British tanks destroyed caused the Germans to pause in anticipation of perhaps a stronger thrust. Kesselring belatedly arrived in North Africa and tried to cheer up Rommel but the Desert Fox knew the game was up. With the failure to exploit the successes won on the initial days and the stiffening allied defenses, as allied reinforcements flowed to the front, Kesselring approved Rommel's request to call off the offensive.

It is likely that only Rommel and von Arnim's failure to cooperate prevented a potential Allied disaster that may have destroyed the entire Allied army in western Tunisia or at least resulted in Allied forces thrown back well into Algeria. As it was all the Germans really accomplished was to bloody the American's nose. During the Battle for Kasserine Pass and of the 30,000 American soldiers who fought in the eight-day battle over 7,000 were killed, wounded or captured. The Americans also lost 183 tanks, 104 half-tracks and 208 artillery pieces - though the equipment losses were easily replaceable. The Germans suffered only minimal losses; 1,000 casualties including only 201 dead and 20 permanent tank losses. On paper, it was an Axis victory, in reality, and with the decision to call off the attack; the entire adventure represented an exercise in tactical irrelevance.

Rommel's failed offensive at Kasserine Pass had been the last throw of the dice for the Axis armies in North Africa.. The Axis armies in Tunisia sat trapped between two powerful armies and reliant on a logistical chain perpetually in crisis, as the Allies enjoyed overwhelming naval superiority and new air bases in Algeria and Libya from which to launch attacks on Axis shipping. By the spring of 1943 the Axis logistical situation had deteriorated so quickly that Arnim actually surmised Eisenhower did not even need to attack his army, as the Axis forces in Tunisia would starve by July. The only realistic Axis option left was withdrawal and thus the chance to save most of the quarter of a million soldiers and the huge stores of equipment and supplies maneuvered into the North African dead end, but this was not what the Axis leadership had in mind. The stage was therefore set for a "second Stalingrad".

by Steven Douglas Mercatante

Post new comment