The Fall 1944 Struggle Along Germany's Western Border

The fall of 1944 ranks among the most difficult months the United States Army experienced in the entire 20th Century, if not her entire history. Along the center of the Allied front, along the German border near the medieval city of Aachen, General Hodges VII and V Corps endured one shattered rifle division after another. Aachen was the first significant German city the allies captured in the war, with a population of 165,000 people. Though the city itself was secured on October 21st heavy fighting raged on regardless; in the primeval Huertgen Forest blanketing the hills surrounding Aachen.

Although only 10 miles across and 20 miles deep the Huertgen Forest bore witness to some of the most brutal fighting during the war in northwest Europe. Crisscrossed by deep ravines and valleys, the dense forestland in the region marked one of the wildest parts of the Ardennes-Eiffel forestland - where Belgium, Germany and Luxembourg come together. All told, from September 14th to December 13th the United States Army committed five infantry divisions (1st, 4th, 8th, 9th, and 28th), an entire Combat Command from the 5th Armored, and numerous supporting units totaling over 120,000 men to win an advance totaling just over 20 miles. Nearly a third of the men committed to battle were either killed, wounded, captured, suffered debilitating physical illness, mental breakdown, or will never be found - 33,000 men became casualties of war. Although the allies struggled across the western front, few operations proved more poorly planned and led and none more costly during the fall of 1944. Nevertheless, the allied armies had struggled across the entire western front.

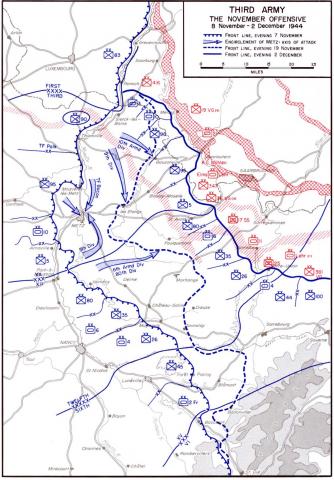

Meanwhile, Patton's Third Army, far south of the debacles in the Huertgen, slowly and stubbornly blasted its way through the Maginot Line's powerful forts. From September 5th to November 21st the fortress city of Metz held out against The Third Army's most strenuous efforts. By the middle of November Major General Walton Walker's XX Corps comprising the 10th Armored Division, 5th Infantry Division, and 90th Infantry Division had spent the better part of two months hammering away to almost no avail at a couple of poorly trained German infantry divisions and the under strength 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division. The German defensive efforts ended up exhausting Walker's Corps and resulted in Patton ordering the US 95th Infantry Division into the meat grinder at Metz where it ultimately played a pivotal role in the ancient city's capture.

Why Patton insisted on stubbornly blasting away at Metz, a fortress comprising some 43 smaller mutually supporting interconnected forts, remains a question debated to this day. Patton's attempts to take Metz meant only 86,000 German soldiers in Lorraine tied down an allied army a quarter of a million men strong. As a testament to the difficulties the Third Army faced during these months one only has to look to the fact General Patton's Army had liberated 40,000 square miles of territory in the heady days of August and September. In October, the Third Army had only freed 125 square miles of territory. Fierce German resistance and allied logistical difficulties had slowed Patton's advance to a crawl, and inflicted approximately 50,000 casualties on the Third Army. Even further south than Patton, the American and French armies under General Patch pushed up to the Rhine, taking Strasbourg on November 23rd. The intensity of the struggle along the German border sent morale plunging in the allied armies. Desertion rates soared. By January 1945, the US Army officially recognized there were approximately 18,000 AWOL (Absent without Leave) Americans, joining the estimated 10,000 British soldiers who had abandoned their duties and went underground in an attempt to escape the conditions at the front. For armies lacking the necessary manpower for replacing the dreadful casualties in the allied infantry battalions these figures boded poorly for future success.

The slugfest that began in mid-September on Germany's western borders had proved markedly different from the breakout days enjoyed by the allies from August into early September. The fall fighting proved why numerical superiority alone did not bring success on the Second World War battlefield. The German army had once again demonstrated its remarkable ability to bounce back from an outright rout, and fight a stiff and ferocious defense against a quantitatively superior army. Even more remarkable was the numerically inferior and overmatched Germans held the allies at bay as Hitler held in reserve the most powerful German divisions and armies. Armies held in reserve in preparation for one more German role of the dice.

by Steven Douglas Mercatante (Map Courtesy of US Army)

Post new comment